Or Is He Both: A Dramatic Close Reading of Immortal Hulk #1

Originally a video essay script, welcome to me having too many emotions about this comic book issue.

The first issue of Immortal Hulk is precisely what it should be: it’s a foundation piece. It asks a question that’s very historically “Hulk,” with the usual full line of questioning being “Who is the Hulk? Is he Bruce Banner or another personality? Or is he both?” It’s a line of questioning that’s centric to the character in terms of his identity and his responsibility for what happens while Bruce Banner is transformed. And everyone, both in-universe and out, has a different answer at any given time.

So before we get into how Immortal Hulk and Al Ewing begin to answer that question, let’s look at how it’s been previously responded to see the differences Ewing embraces in the character. The answer depends on a couple of variables:

First, who is writing the Hulk?

Different writers have different ideas when it comes to the Hulk. That one is an obvious answer, but not one that seems to be acknowledged very often outside of people who really like the Hulk.

Some writers utilize the Hulk as a force of destruction only, a conflict-piece in their game. You see this most often when he’s making a cameo or appearance in another character’s run. The Hulk is a sometimes-bad guy in the hands of these writers, with the Bruce Banner aspect not being taken into account unless the hero in question cares about Banner (with this being summarized as an “Oh I gotta stop the Hulk, so Bruce doesn’t feel guilty later” song and dance. Like an exaggerated form of stopping a drunk relative).

Some writers take that in a more sympathetic direction, having Bruce Banner be the victim of the Hulk. He’s a victim of a condition. That view characterizes Banner and the Hulk in massive ways that stick with the character throughout his incarnations. Even when he’s a sometimes-bad guy or a force of destruction, writers who handle Hulk this way will utilize the first type of actor’s events and then give us Banner’s reaction to knowing the kind of damage the Hulk did. Depending on the writer’s talent, we can see a fascinating human response to the damage they inflicted while enraged. That’s a feeling many audience members can relate to, making an emotional mistake and then seeing the fallout caused by that mistake. However, these instances are where we can sometimes get frustrating depictions of the Hulk being a mental/chronic/both illness allegory handled with the same care as the X-men being a racism allegory. And Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde inspire this perception. Even Stan Lee’s said as much in an interview with Rolling Stone, stating:

“I was getting tired of the normal superheroes, and I was talking to my publisher. He said, “What kind of new hero can we come up with?” I said, “How about a good monster?” He just walked out of the room. I remembered Jekyll and Hyde and the Frankenstein movie with Boris Karloff, and it always seemed to me that the monster was really the good guy; he didn’t want to hurt anybody, but those idiots kept chasing him up the hill until he had to strike back. So why not get a guy who looks like a monster and really doesn’t want to cause any harm. But he has to in self-defense because people are always attacking him.”

It’s pretty interesting, from a creator standpoint, to hear this origin for the Hulk! Given that Jekyll and Hyde, Frankenstein, and the Hulk all echo real-life fears with scientific advances in different fields and eras, it makes a lot of sense that the three are more related than most give credit for. However, what isn’t that great is when writers take the Hulk — who by design isn’t a typical superhero — and put him with regular superheroes and have his powers and his state of being as a “condition” to be cured rather than who he is as a person thanks to the trauma of his origin story.

But then you have the last category, which includes Greg Pak and Al Ewing, of writers who approach the Hulk as they would any other character, by taking in the trauma, the pain, and the experiences the Hulk has had and let that shape how they write the Hulk. For Pak, you see this strongly in Planet Hulk and World War Hulk with how he had a very person-y Hulk front and center. The typical “Hulk Smash” dialogue pattern is usually discarded because it distracts from the type of story they want to tell, which are first and foremost stories about a person. It might be a person who turns into a giant super-strong version of themselves at particular emotional stimuli, but still a person. Planet Hulk, World War Hulk, and Immortal Hulk are all, at their core, stories about who the Hulk is as a person. And the undeniable and simple fact is that people don’t talk like “Hulk Smash!”, “Hulk no like you!”, etc. That dialogue pattern is useful when you, the writer, want to establish the Hulk as something very Other very quickly. It’s a shortcut. But it doesn’t help portray the Hulk as someone we the audience take seriously as an adult character, even if you’re taking the mental illness route. Maybe even especially if you’re taking the mental illness route; the pattern doesn’t match up with a lot of verbal processing struggles that I know of (quick acknowledgment that my experience is not universal; I used to work as a secretary for a speech pathologist, hence the observation). The three Hulk storylines I mentioned are notable character-shaping stories for the Hulk, but these three are the best examples I can think of for this type of Hulk storytelling. There is equal care placed between the Bruce Banner persona and the Hulk persona, and there’s usually an examination of both of them and what they mean.

And any time that there is a moment of stillness, of reflection, in superhero comics is a moment of joy because you get to see the weight of the fight genuinely affect them.

Allowing a character a moment of stillness between the world-threatening events allows the audience to see the character as they are because there’s entertainment in seeing characters simply exist in their day-to-day lifestyle. Planet Hulk does a beautiful job balancing stillness and action so that the sheer anger expressed in all of the action of World War Hulk is genuinely appreciated.

When is the specific Hulk run you’re talking about being published?

Like typical literature, time periods affect a lot of what influences comics (the Hulk included; look at Captain America 30 years ago versus Captain America today. They’re two entirely different characters. Another example: Batman in the ’90s versus the early 2000s versus today; they’re all very different). You’ve got early-day Hulk published in the ’60s, with nuclear threats on everyone’s minds, counterculture, and anti-war sentiments. You can see a little bit of the latter in Hulk’s main villain, General “Thunderbolt” Ross. Then you’ve got the rest of the Hulk’s roller-coaster history, where you can see how sympathetic his character is depending on various beliefs of that time. Standard variables of real-life culture bleeding into the Hulk include: if mental illness is commonly hyper-demonized in that period, if a more pro-military stance is taken (General Ross being a good litmus test of that), and more. That analysis would be its own essay, so that’s as much detail as I’m going into here.

If it’s in-universe, what character is talking about the Hulk?

In-universe, the Hulk is a controversial person. He’s got great friends, bad friends, and enemies galore. A few in-specific people that usually have their own runs or are a part of team runs that don’t include the Hulk:

- Tony Stark, aka Iron Man. Tony has a history of projecting his issues onto Bruce and attempting to help. Remember my drunken relative comparison earlier? Yeah: a lot of this is Tony projecting his old alcoholism onto Bruce’s condition with the Hulk and trying to help with sympathy and actionable help. This help isn’t always actually helpful: Tony Stark’s support for Bruce ranges from helping to pay for damage repair for Hulk’s rampages to help his buddy sleep better at night to actively launching him into space with the intent of putting him on a lifeless planet. As a result, Tony Stark falls into a “bad friend” for Bruce. There’s also the awkward fact that Tony was sleeping with Bruce’s cousin, She-Hulk, for a while and used that connection to rip her powers away. I don’t know if the two ever actually address that, even in a throwaway line. I can’t imagine it smooths out their friendship, though.

- Reed Richards, aka Mr. Fantastic of the Fantastic Four. There’s a whole video to be made about Richards actively being one of the most “villainous” people in the Marvel universe, with his scientific endeavors and loose morality and dickhead personality. All of those are things that have yet to be meaningfully addressed by the by; status quo says he is a good guy and thus, a good guy he will remain, even if he is more interesting as a villain). He falls somewhere between “bad friend” and “enemy” for Bruce, having been involved in the whole shooting him into space affair and commonly being one of the heroes that he has to fight when the writers are using the Hulk monster of the week.

- Ben Grimm, aka The Thing of the Fantastic Four. Honestly, somewhere between “great friend” and “bad friend,” depending on what the writers are looking for. He’s sometimes one of the only people who really understand the Hulk, not Banner but the Hulk, but he’s also sometimes the person who uses that understanding to hurt the Hulk rather than help him.

- Walter Langkowski, aka Sasquatch of Alpha Flight. Put a pin in that Sasquatch; we’re coming back to him in Immortal Hulk issue #3’s essay (he’s also probably getting his own essay because I have Words about this man). But, for now, he falls squarely into “bad friend” territory.

- Sentry. Defies categorization because Marvel can’t decide what they want out of Sentry (in my initial draft of this essay, I had a joke about Sentry being on the Ebony Dark’ness Dementia Raven Way bus out in space, putting his middle finger up at the Avengers. However, since the initial drafting of this script, he has entirely died. We’ll see how long that lasts). He’s either Superman and Adam Warlock’s love-child or the edgy variant thereof. He’s had good moments with Bruce, with his powers working to help soothe the Hulk, but he’s also had times where he believes that the Hulk is a threat to society. It really depends on the writer and the kind of metaphor they’re pulling out of their ass.

The natural, general pattern is that if the character isn’t from the Hulk comics themselves or Hulk-adjacent (a gamma mutate, for example), that character will fall into the bad friend or enemy territory more often than not. Walter and Hulk villains are exceptions to this rule, mainly because the vast majority of them are absolute assholes.

Is the Hulk not the main character of the instance you’re talking about? Whose run does he appear in?

- Fantastic Four? Commonly berserker for the Thing to tangle with.

- Iron Man? Commonly “Bruce, we’re friends, stop fighting me” with little to no acknowledgment of the Hulk as his own entity. Typically takes the “stopping a drunken friend” framework up to 11, which is kind of gross considering Tony’s history as an alcoholic because if we’re making that comparison, Tony should be the most sympathetic and understanding of Banner and the Hulk.

- Avengers? Commonly the muscle and/or comedic device. Sometimes has a sweet, friendly rivalry with Thor over who is the strongest Avenger that’s played up for comedic value.

- Defenders? No, not the Netflix Defenders, the original Dr. Strange-Hulk-Namor team-up that had Silver Surfer sometimes. They’re barely a team, don’t hold your breath for much of anything with Hulk being positive here. Mostly muscle and a very literal set of hands for Dr. Strange. Very rarely, I think, you’ll see Namor and Hulk have bro-jam moments of being anti-heroes (which like…treasure those. They’re so good. Honestly, where’s my Hulk/Namor crack-ship content where they do so many counterculture protests?).

So we have all this history for the Hulk, and that’s not even touching that Bruce Banner decided to convince Hawkeye, a friend of his, into killing him in Civil War 2 (I haven’t directly read Civil War 2, since I saw the title and premise and skipped out on it for the sake of my mental health). Immortal Hulk #1 had to be a firm answer to all this history since it’s the character’s return to being alive in more than one sense: it’s Bruce Banner’s first solo run since his death. Al Ewing had his work cut out for him, but it’s nothing he’s not used to, given his history with Loki: Agent of Asgard. Even knowing his work on You Are Deadpool, I figured he would do something unorthodox with Bruce Banner and the Hulk.

But nothing could’ve prepared me for Immortal Hulk #1.

Each issue of Immortal Hulk has a quote that accompanies it. Issue 1 goes 60 mph right out of the gate with a quote from Carl Jung:

“Man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself or wants to be.”

Keep that quote in mind while I discuss everything else in this issue. It’s not an aesthetic throwaway quote that’s fake deep; it actively means something to this issue and to Ewing’s Hulk as a whole.

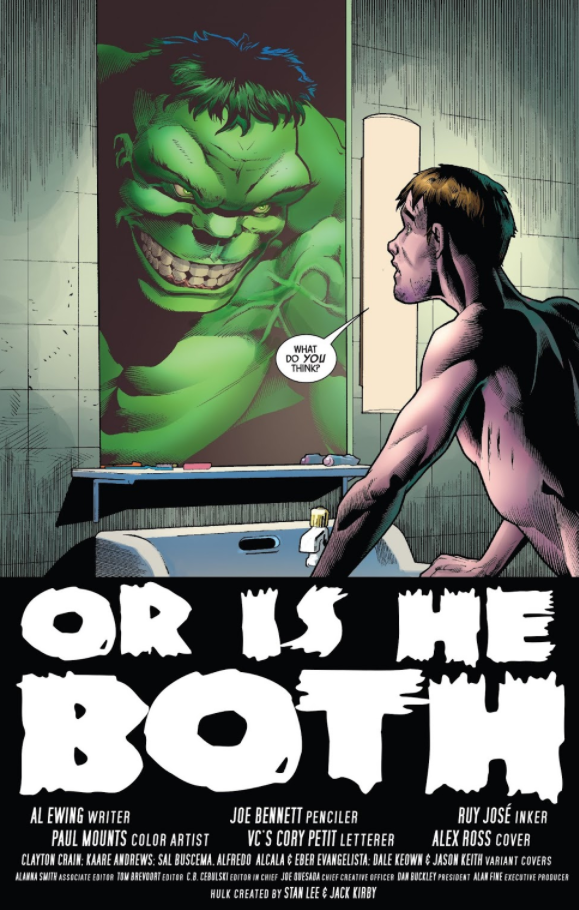

Between Issue 1’s title “Or Is He Both” and the very first line from the issue — “There are two people in every mirror.” — we have an answer to how Ewing is going about the Hulk. Bruce Banner and the Hulk are two people. As the panels continue to go, we get a continuation of the mirror line.

“There are two people in every mirror. There’s the one you can see. And then there’s the other one. The one you don’t want to.”

The shot-for-shot panel work here is phenomenal. The artist for this part of the run, Joe Bennett (disclaimer from the future of when this was written: I hate Joe Bennett as a human being, his skills here are good, but could also be done by someone who isn’t a blatant antisemite and racist), spaced this out beautifully. The panels provide a slow build-up to the run’s main character, the man we arguably bought the issue to see, and then assert that we don’t want to see him.

Now, I want to take a moment to discuss the teenage girl that appears at the very, very beginning of this issue. When we’re introduced to her, we have no idea what her name is. We know she’s on some type of trip with her mother, that her mother wants her to be healthy, and she has a pretty stereotypical pre-teen rebellion against her mom’s concern. She’s a person you can imagine seeing for a snapshot of a second in real life, at an actual gas station. Gods know, when my family used to go on the seemingly endless road trips in my childhood, I saw at least 15 of these pre-teens of all genders within 13–14 years. She’s unafraid, even as she shares the same space with what the opening narration is proposing to be the man we don’t want to see. She gets her apple juice, just like her mom asks, and declares Bruce to be a creep. I’d like to propose that she is the audience insert for this issue and this issue only. This girl asks questions the audience is — “What’s his deal?” — and her line of sight is used to bring the audience’s attention to another question, written on the cover of a tabloid magazine.

Ewing proposes the audience to ask: “Do the Avengers know that the Hulk is alive?”

And right as these questions are asked to the audience by this girl, she’s shot. She dies. The potential audience stand-in character we’ve been quickly, subtly introduced to is dead. And her death is what sets off a scene we’ve seen in Hulk media again and again: Bruce Banner witnessing injustice and getting angry. His eyes light up green, and in any other Hulk run, we’d be seeing rippling muscle and fists.

But instead, Bruce gets shot in the head in the middle of his stuttered accusations.

No heroic speech, no pathos-ethos hybrid challenge of “how could you,” just violence. We expected violence to respond to the girl’s death, but we assumed that violence would be delivered for justice from years of history with the superhero genre and the Hulk.

But this is Immortal Hulk. There’s no time for that. We see the robber, the murderer of three, run out, and the mom immediately connects the dots.

The girl is Sandy. Sandra Ann Brockhurst. Twelve years old. Keep a pin in those details.

We’re left with a detective and a reporter who are both talking about the robbery. The detective, Detective Mayes, is freely giving out details to the reporter (who we’ll get to shortly) in hopes that tongues will be loosened so justice can be dealt with. The security footage is blurry, there are no actual witnesses (Mrs. Brockhurst only remembers vague details), and the most evidence they have is the bullets from the bodies. Bullets that will take ages to analyze because they’re being shipped from Arizona to West Virginia so they can be matched up with some paper records. This sentiment is the start of Ewing’s run, pointing out systematic problems with America’s justice system. “CSI by way of the gun lobby,” indeed, Detective Mayes.

Two crucial things happen next: our reporter is named (Jackie), and it’s delivered in this transition quote:

“Don’t act surprised, Jackie. You’ve been a reporter long enough. You see how the world is. Even if maybe…maybe you don’t want to.”

Bennett’s at it again, with the help of Cory Petit. This gorgeous chorus of talent from these three artists (Ewing, Bennet, and Petit) really, really make this scene. I don’t personally know if Ewing made notes for what to be bolded or how to space out that quote over the art or if Bennet made those decisions and Petit augmented them, but the talent of these three men really shows in this scene.

The transition with this quote for the audience to see the dead body of Bruce Banner slowly hulk out (wonderful color-work by Paul Mounts on the arm, by the way) as the text box reads, “…maybe you don’t want to.” is just…I don’t know how to analyze this bit without full-on fangirling. It showcases a solid understanding of the tools at the team’s disposal.

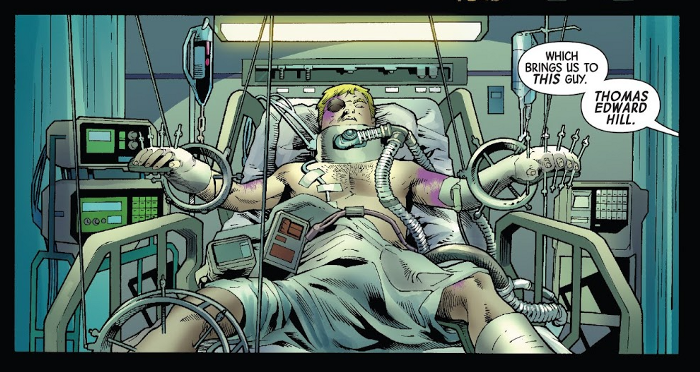

Now, remember how I said that Sandy is the audience stand-in? I want to make a similar proposal to that. The man who robbed the gas station? Who killed her, Bruce, and the man at the cash register? I’d like to propose that he is a thematic foil to Bruce Banner, with the gun in his hands being parallel to the Hulk. I make this proposal because in the scene immediately after it’s suggested that the Hulk is still alive despite Bruce being shot in the head, we see the following quote from the robber (who we later know as Tommy):

“I didn’t want to do it. I just…I heard something fall, and I turned, and it just…it went off in my hands. And then I…the others, they, they saw me…I didn’t think. I swear I didn’t think. I was scared, I…I panicked. I didn’t want to do it.”

Now, take in his physical design. Tommy’s a white man, built spindly, like how we see Bruce drawn in this issue. He’s in the same kind of cheap but comfortable clothes we’ve historically seen Bruce in any time there’s a “Bruce is on the run because he’s been wrongly accused” stint in his runs past and even in this issue. Something else I want to draw attention to for this is the implied name of the gang whose hangout he’s in: Dogs of Hell.

Now, dogs of hell or hellhounds have a mythological tendency to guard the underworld and hunt down lost souls. They’re supernatural creatures with abilities not seen in their regular mundane counterparts. I propose that the Dogs of Hell in this issue are a micro-level, mundane inverted mirror for the Avengers, who guard the world, hunt down people who that the justice system loses, and have supernatural abilities not seen in humanity. And that Tommy is a micro-level mirror of Bruce Banner, who just did his first mission for them.

In the golden age of comics, the Avengers didn’t care about the property damage they caused. They just cared about the bad guy they brought in. Similarly, the Dogs of Hell don’t care that the robber killed three people in his first bank robbery, just how much cash he managed to get.

I think what cements this interpretation for me is this quote from the Dogs of Hell leader: “You’re not a bad guy, Tommy. So…I’ve let you slide a little, y’ know? Just ’cause I like you.”

This sentence is a sort of sentiment brought up by Jackie, the reporter, to the Hulk in Issue #11: that he gets to be so angry, so destructive, because of how the people in charge of the system like him. The Avengers like him. They pull strings for him, just like how the Dogs of Hell leader has used his position to let Tommy’s inability to pay back his loan from them slide. And, given how the Avengers often hurt the Hulk to eliminate the threat he is, this string-pulling is done laden with a warning: if you don’t pay me back with what I want, then I’ll have to hurt you and your support network. For Tommy, that’s money, and his support network is his family. For Bruce, that’s with fitting into their norms and “getting better” (being neurotypical) and his support network usually being other good-aligned gamma-mutates.

The rest of the Dogs of Hell leader quotes hammer this point home: “You want out of this hole you’re in, you need to toughen the hell up! Don’t be weak, Tommy! ’Cause somebody stronger’n you is always gonna come along and — ”

There’s something to be said with male neurotypical thought processes and the societal need for men to be strong even if they’re in a state where that’s hard (such as in mental illness). It’s normal for men to try to bottle emotions up, only outputting rough and tough emotions. And this is something you can see mirrored in comic audiences and their responses to emotion: anger is celebrated, sorrow is only tolerated when it’s too big to ignore or strokes a male ego (i.e., male characters being angry when a female one is fridged), but anxiety and fear are things to be laughed at. Instead of taking the full spectrum of emotion to appease their audiences, superhero comics (and media in general, it’s just more noticeable in superhero comics) usually have to stay within these pretty rigid guidelines. The fact that we see this kind of sentiment coming out of a morally wrong, static character is pretty damn important. It’s the narrative condemning that sort of thinking.

Especially with what happens next.

The Hulk arrives. The audience doesn’t see his arrival so much as feel it like Tommy and the Dogs of Hell do. And right away, we understand that this Hulk is different. Not just because he can bring Bruce Banner back from the dead, but because he’s smart: he goes after the gang’s generator first to draw them out. Used to be that the Hulk had to be directed by someone else to do something that tactical. And he moves in the shadows, like a horror movie monster. He picks people off, a few at a time. You could replace the Hulk here with horror movie monsters and still have a complete story.

Ewing invites you to do so by having one of the gang grunts refer to this Hulk as “the Devil” and “the damn King of Hell” with the gang’s leader responding how the skeptics in the audience would “no, that can’t be right, this guy’s just a meth-head. I mean, this is the Hulk; he’s never that bad”.

And then the Hulk’s hands crash through the wall, like a horror movie monster’s claws, and grab the gang leader by the head, presumably killing him.

The panels follow Tommy as he runs. This whole day has been filled with terror and horror and violence. He hears the Dogs of Hell, the most hardened people he knows, trying to stop this monster. Guns do nothing to it. Even going for the eyes does nothing. He goes to unlock his car, hands shaking as he hears the shouts behind him.

“I know what you are!” He drops his keys, frantically going under his car to get them.

“I know what you are, you son of a bitch! You’re him! You’re the — ”

Tommy turns around as silence fills the night air. He aims his gun. “Hello? Is…is anyone…still…hello? Anyone?” Silence. He’s sweating in fear as he hears nothing. He sees a shadow cast over him and sees our main character.

The Hulk, perched on his feet and leaning down to address Tommy, says, “Sandra Ann Brockhurst.”

And historical precedence with the Hulk dictates that everything we know about the Hulk is wrong. This Hulk is different. He mirrors the statement of the detective, the weary and tired symbol of justice. “She was twelve.”

It’s this moment of this new Hulk looking down at someone who mirrors who he used to be. I know I’m repeating this, which might grate on some nerves, but I can’t emphasize enough that this is a Mirrored Conversation. The Immortal Hulk is talking to the Bruce Banner he used to be, the one the audience used to know and who the general audience knows, but in a new skin with different circumstances. Like, remember when I was doing my recap of the Hulk’s history and how some writers used Hulk and Banner to cement the human condition, to give the audience that catharsis of “I made this mistake out of emotion, I regret this.” To witness someone else do it on a larger scale, making us feel better about our in-comparison micro-level lashing out?

This Hulk points out a different point of that same cathartic image:

He explicitly asks, “How does the gun feel in your hands? Heavy, right? All that stopping power. Heavier than it is at the range, even. You go to the range much, Tommy? Shoot the paper targets? It was heavier in the gas station, I’ll bet. With other targets. No? All that power, right in your hand? There wasn’t some little part of you wondering? Wondering what you could do. If you let the power loose.”

The question I asked myself the first time reading this issue was, “Are you talking to Tommy still, Hulk, or are you talking to yourself?” Because it’s hard to tell, knowing what I do about the Hulk. But then I remembered the title of the issue: Or Is He Both? A third option. He’s doing both because either way, he’s damning and right. It kills the catharsis of the old Hulk, who got away with the emotional outbursts because when framed like that, the old Hulk doing those things is a villain. He’s no better than Tommy here, who snaps again as he’s called out and tries to shoot this new, damning Hulk.

It doesn’t work. We can viscerally see the effect bullets have on the Hulk this time: they leave dents but nothing else. Not even bruises. Like this new Hulk isn’t alive. This massive judge, jury, and potential executioner just smiles at this, casually finishing his sentence, “You know. On someone who deserved it, I mean.”

This is such a neat callout, both in the text and in the context of who is saying this. That’s been the justification of so many off-the-books vigilantes in superhero comics: they get this great power, and their first thought is how to take that power and hurt people who deserve it. It was the saving grace of the Hulk for a while because Bruce could justify all that violence by saying, “I let the Hulk go to town on people who deserve it.”

And before we can even start trying to answer “does Tommy deserve this” or “did those people Banner did this to in the past deserve this,” the Hulk continues, “Know how I found you, Tommy? Because ever since you pulled that trigger…you’ve been lying to yourself. And I can smell a liar.”

That is such a loaded line to say, with all the meta-context! I could do a whole little ramble about that, pitter and patter about this Hulk calling himself (and Bruce, but both) out. This is an entire ass (not a half-ass, not a quarter-ass, a whole-ass) callout to himself, his history, and everything, which is a HUGE theme of the Immortal Hulk: this isn’t a hero, this is someone who makes mistakes, and people are reacting to those mistakes, all set in this larger than life scale setting because sometimes, you gotta itch that metaphor bug and get really not-subtle with the metaphor and swing big and loud to get the point across. But also, sometimes you are a comic book writer hired to write the next chapter of a franchise character who does not get to die, and that franchise character comes with baggage.

And Al Ewing just goes, “I’ve got double proficiency in baggage as a weapon, let’s fucking dance.”

Tommy scales up on the promises, the regret, that he knows what he did, that he’ll go to the police, that he’ll tell them everything, go to jail, repent, he’s got a family, a little girl of his own, he just needs to live. And we see him say this all while in the eyes of the Hulk, as we slowly move closer and closer, scaring him to fall back onto the stairs behind him.

The next page- gods, the next page, we get a perspective reversal. We look up at the Hulk now, as he responds to this fear, this repentance; “You don’t say.” The Hulk, slowly getting closer, towering over Tommy (and us, the audience) as Tommy continues to beg for his life.

The facial expressions of the Hulk kill me here, Bennet’s use of the subtle tells of the Hulk’s face (look at these panels, around the eyes, the mouth, as it transitions through Tommy talking about the Hulk making mistakes too and asking “I’m not a bad guy. Am I?” This is just such fun subtle storytelling, through the face, especially with later reveals about this Hulk).

We cut away to Detective Mayes and Jackie talking about the aftermath of the Hulk’s attack on the Dogs of Hell and Tommy. We see the damage through a mundane perspective, devoid of the action. The Dogs of Hell are stable: despite all the movie monster action the Hulk was pulling, that lot ended up with mostly concussions and fractures, but the most important thing the Hulk gave them was fear. Detective Mayes talks about how they knew the Dogs were into drugs and organized crime but how they didn’t have enough evidence. Now, though, they have the whole gang willing to talk because of what the Hulk did. Put a pin in that because it ties into the Immortal Hulk’s plotline of the authorities not having the power to affect change, but one man with the right motivation and power does (for weal or for woe).

The Hulk ended up bringing him and his gun along to the hospital, leaving him in a crater. It’s uncertain if he’ll walk or even wake ever again.

This is a Hulk who will not stand another like him. This is a Hulk who plays judge and jury, who does not want to watch another man like him grow and stumble.

This isn’t the Hulk the setting or the audience is used to.

Just to drive the parallel between Thomas Edward Hill and Bruce Banner home, Issue 1 ends on this powerful, promising imagery:

It’s such strong Hulk imagery and question, that we the audience can identify as the Hulk’s, but done in such a way that’s new and refreshing.

The Literal Last Page of the Issue, I Cannot Even-

There’s more to this issue: it’s the introduction to Jackie, who will be a mainstay of Immortal Hulk and serve to provide one of the best foils for Bruce Banner that I’ve ever seen.

I’d also recommend reading Immortal Hulk on your own. I plan to do three more of these dramatic analysis essays on Immortal Hulk and, if you read along, it can kind of be like our own book club. I’m thinking…issues 2 and 3, then jump ahead to issue 11 (a screencap of 11 was what got me hooked on the series).